The name says it all, it’s a classic. Located on the Route d’Oron in Poliez-Pittet, just above Lausanne, the first time you hear about the workshop and its founder Christian Tedeschi or the address, you wonder if you’re not headed towards another planet, and as a matter of fact, you just might be.

Getting to the place is easy, but hearing about it or what happens in there is a different story. Switzerland, just like its banking system, is pretty secretive and that applies to most workshops, Auto Klassiker being no exception. Upon arrival, a look through some of the windows may give you a little insight in what is going on but not more, it’s only once you are past the front door that you realise you’ve just reached that alien world.

Christian Tedeschi is the founder and owner of the place. A self-made enthusiast who transformed his passion for the cars into an everyday job and workshop, looking after some of the most beautiful and rarest examples you could ever think of. As of today, we’re surrounded by a plethora of high-end classics, and there’s only two words to describe the variety of cars and workmanship on display: quality and skills. These words pervade everything at Auto Klassiker, lending the place a very special feeling. Let’s take a closer look.

Christian is someone I would describe as a friendly Swiss man, but my opinion might be biased as I’ve known the character for more than 10 years. Surely he’s an eccentric figure in the classic scene, travelling Europe with proud and distinctive colours, those of Switzerland. If you see a car bearing Swiss cows, or smell a fondue at the back of a garage, that will be him. Take a little time to stop by, just like I did a long time ago, and he will share his words, stories, and passion about the cars in a unique way.

Auto Klassiker started in Lausanne, back in 1989, to turn Christian’s childhood passion into a job. His father liked cars, bikes, and pretty much all things with an engine. As a four-year-old boy, he took part in his first rally on his father’s knees around the Lac de Neuchâtel aboard a Martini, a car which originated from St Blaise, just like Christian himself. That’s probably what started it all, but Christian recalls other influences such as the likes of André Wicky in his Porsche going up the Marchairuz hill climb, or the first Tamiya kit he bought aged 14 years old in 1973, which was a McLaren M8. Some 40 years later, he would be racing an earlier M1 model all around Europe to echo those younger days.

As his passion grew, he acquired the skills required to run a workshop full time, and he chose his passion over everything else. It started with a BMW 2002 Tii, which he bought with a broken engine, taking on the job to rebuild it himself alongside his apprenticeship in catering and his life as a ski instructor. The budget was small but he made up for it with enthusiasm. It always seemed to be about learning with Christian – his skills were not innate, but acquired and throughout his life – still to this day he studies the latest trends, be it for engines, suspension, coatings, or whatever else catches his interest. In the end, it doesn’t matter what it’s for, as long as the work done in his workshop can be improved.

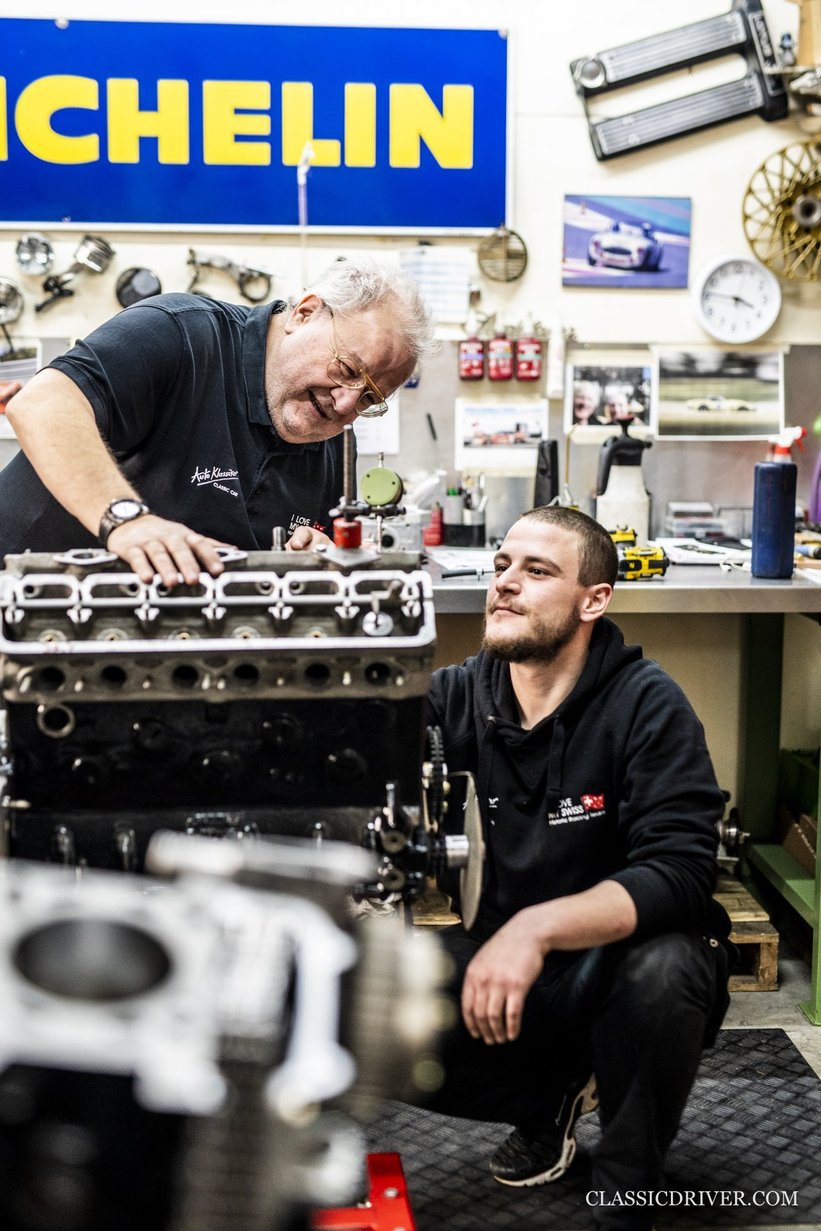

Relying on a team of four including his son Michael, there is no limit to what cars you will find, ranging from Pre-War to the early nineties as of today. It’s not just a workshop, but more of an open encyclopaedia as every case is a different one, fine tuning, detailing or A to Z projects, the work is and skills are both amazing, giving the impression that at Auto Klassiker, anything is possible.

So Christian, there’s a huge amount of variety in terms of the techniques and skills on display here, could you tell us more about it?

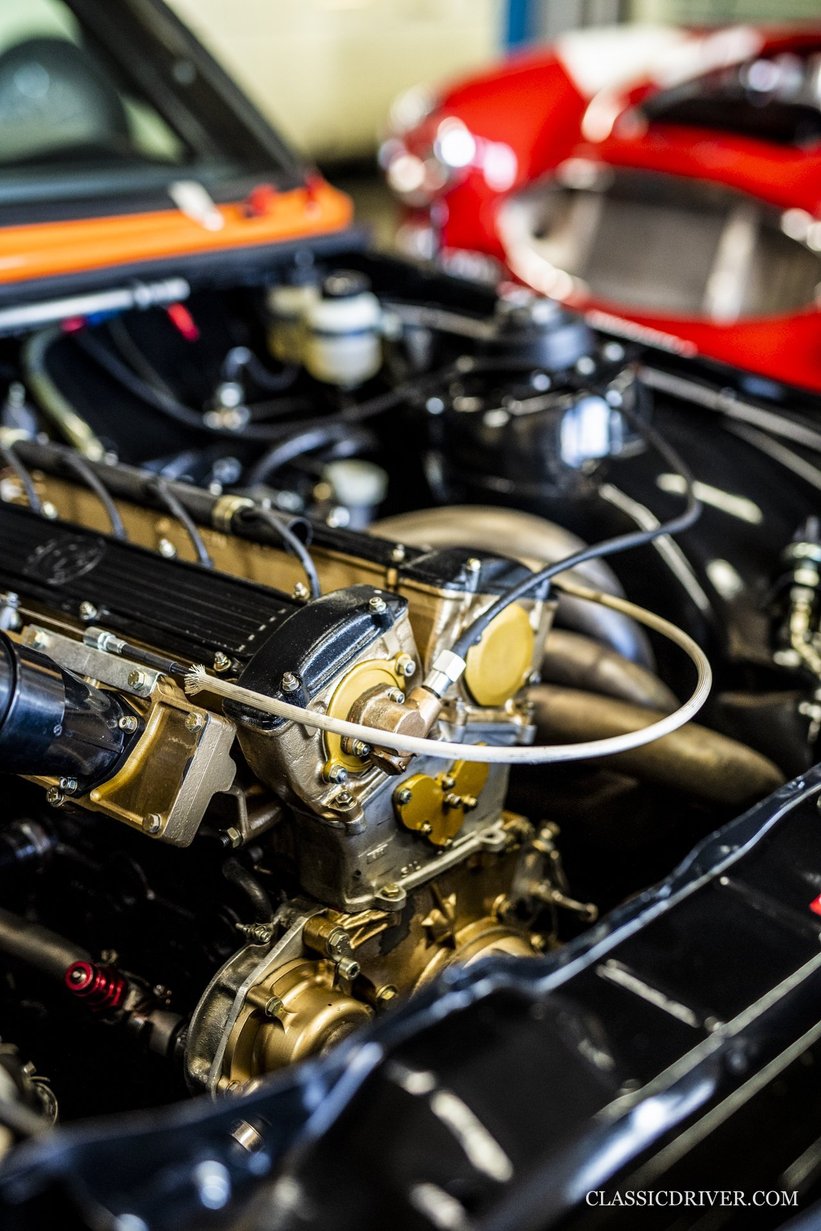

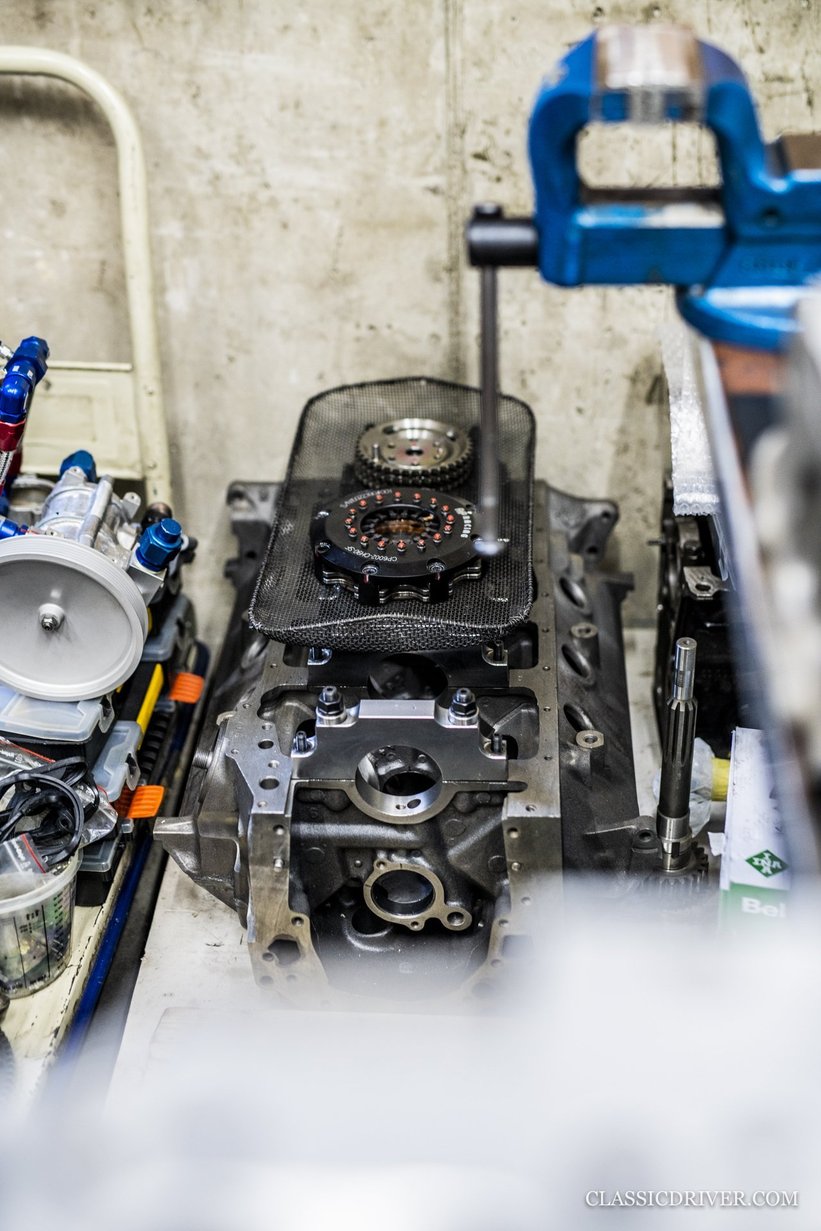

Well, all cars are interesting to me, from Pre-War up to the very latest models. The evolution and technical aspects of the cars are the primary interest and passion, but our specialty here is to master any technique and the ability to develop and fabricate whatever we need so that we can get the cars out. This is what I’ve worked on ever since I started the business in 1989, maintaining the period and historical aspect, but making sure that the cars of all eras and ages can be comfortable and safe on the road through the application of modern skills and technologies. Our developments are about materials and quality when it comes to machining, coatings or the understanding of specifics applicable to dampers, engines, transmissions. All that enhances the product and allows for improved driveability, be it on the road or circuit, and that is our main brief when a customer comes past the door.

In a way, what you’re saying is that it’s all about learning and transferring that into the work?

Pretty much, yes. Back when I started, it was a me and another guy in Lausanne doing the job, I took on the work of learning a complete set of skills and selling those skills. Therefore everything is worth learning about, and the things that interest me are the things I haven’t yet done, the challenge it represents is a drug. I read, I learned, took part in seminars, workshops, travelled to meet specialists, worked on the milling machine, did castings myself to improve my understanding, and all that you see today is the result of this quest, learning something new every day as some would say.

But it’s also about the cars, be it road or race cars, they were not manufactured to last as long or to be used as we do today. The knowledge then becomes important, you must restore the cars the way they were built, technique becomes essential to keep them alive or even to bring them back from the dead in some cases, it’s those skills that will allow the industry to continue. History is an important part of the work and something I hope to transfer to the next generation, my son being the best example of that here today.

What you just explained is evident in the variety of cars and the length of some of these projects, we also see that you have a soft spot for competition cars like the BMW, Leyton House F3000, the Austin Healeys, and later Porsches that you have here, is this a living laboratory for you?

It’s an interesting thing you’ve noticed, in a way it can be pictured as a laboratory although history must not be rewritten. The F3000 is a good way to look at historic motor sport, I am known to many for my work on the Harald Grohs BMW 320 Jägermeister car, which I own. It’s the very car that you see flying in the period pictures of the 1977 DRM race at the Nürburgring! That was a whole lot of work to return the car to what it was back in 1977, remember, they were not designed with today’s historic racing in mind, and finding all the details particular to that car took an enormous amount of time too.

So the F3000 was a step further, I thought I had become smart enough to give myself a chance in such a beast today. I’m past 60, so maybe I’m wiser in terms of driving, but above all it’s in a different league in terms of the design and construction, as well as engine and electronics. Yet we’ve managed to do what many would tell you is impossible for reliability reasons, we’re even running it on a period ECU. That’s another example of how we want to work, why do different when time and patience will allow you to have the toy working as it was? It was far from easy, but as a laboratory and learning exercise we did it.

More generally, we try to preserve every car that comes in here, competition, or road. If you restore a car today and you want the best ride possible, you could buy an unobtainable set of dampers to make it better, but why not take the old ones and have them valved the way they should be? It will do the same job but better, as we’ve learned. In the end they are all the same, it’s what you make of anything that becomes the result, isn’t it?

We can tell you have a passion for Italy. The food is one thing, but the Maserati A6G Frua, of which you have two in the workshop, are extremely interesting. Please tell us more about the pair.

Well, we restored the first one for a customer years ago, and the second one came from Norway, an American car originally which ended in a pretty bad state. We’re fortunate enough that the car came complete, and that we had the previous one on-hand to help complete the work. Nothing is simple here and it takes countless hours to actually complete any part of it.

The dashboard is a good example, as are the door panels as nothing exists except the other example to use as reference. Everything has to be made, copied, adjusted, altered and so on. Days are long, but on the other hand, it’s like restoring a fine art picture, the prospect of looking at it once finished keeps the project going.

Another example we have is the 250 Berlinetta. The car has been here for a long time, but it was about finding the correct car to compare and identify differences, finding out what had happened to the car before we started the work, making sure we had every detail straight. We talked history, but every project has its own, it takes time and devotion.

Time and devotion, that is interesting. We see that you also have an another extensive project, that’s a miniature train set in the background of the workshop isn’t it?

Yes, scale trains are one of my passions, and like the cars it has become extreme. The detail and attention I give to that kind of project is also huge. here we have a little summary of all the types of trains you can find throughout Switzerland, it is still a work in progress, but one I do after work, my own secret garden to keep my hands dirty.

Dirty hands, so you’re not hanging up your gloves in the near future right?

I don’t think so. My son Michael is learning and doing a fantastic job here, the learning from scratch and engine work he has done since joining us just a few years ago is impressive, but there are still things I want to do, and then there’s the racing. The projects are still going, we built a Lotus Elan in 26R specification and have achieved some very good results in terms of performance, mastering the twin-cam 16V engine on original castings, building a car that is light. It’s lighter than anything most have done today and yet it’s still in accordance with all the regulations. Colin Chapman would have been proud.

There are the road cars, looking after the ones we already finished, or the ones that are still being worked on, it’s a never-ending story and as of today, no I won’t be hanging up my gloves. I want the new generation to take over, but I have yet to decide when I’ll quit.

Talking about the historic scene, not just motorsport, what are your thoughts on the future?

It has grown, it has become huge in the last 10 years, yet we must treat it respectfully just like the cars. There is an overall sense of hype in the business right now, but we must not forget that this is history and that history must be respected, not rewritten. The cars are what they are, let’s make the most out of them but respectfully. Let’s not make unicorns.

Text by Louis Quiniou. Photos by Rémi Dargegen for Classic Driver © 2022