The mountain was there yesterday. And it’ll be there tomorrow. It has no interest in us. Its sense of time is geological, we’re little more than a moth that has landed on its broad flanks a moment ago: the prehistoric hunters, the Roman legions, the pilgrims and medieval traders, the road builders with their dynamite, the royal carriages, the puffing steam trains, the freezing soldiers with their rifles, the first motorists wrapped in clouds of dust and the echo of their engines, the cyclists and their iron thighs and tight trousers, the honking postal coaches, motor-homes and buses, the roaring racing machines – the mountain couldn’t care less. Mule tracks, military thoroughfares, trade routes, panoramic roads – merely fleeting shadows on its elephant skin. When a wave of rock piles up and breaks in the slowest of all slow motion for a billion years – what then is a decade, a century, a millennium?

The mountain stands still in the raging sea of time. The rise and fall of civilizations, the march of progress and technology in the modern world – for human ambition, the mountains have always represented both an adversary and an incentive. By dividing valleys and villages, countries and cultures, mountains have challenged us. Yet we always found a way. Long ago, it took weeks to conquer the icy summits, wrapped in furs trudging through ice and snow. We feared bears and wolves, we begrudgingly paid the toll charge, searching for the flickering lamps and life-saving hospice at the top of the pass. Now we sit in leather seats as we hurtle through neon-lit tunnels of granite, traversing entire mountain ranges in a matter of minutes, or we fly over snow-covered peaks in climate-controlled aircraft. The mountains, which once seemed as high as the sky, have not only lost their terror, for modern traffic, they’ve now been leveled to the ground. And the alpine roads, crafted by generations of brilliant builders to span gorges and peaks, the stage achievements carved in stone against nature’s superior might? They have turned into adjuncts to our road networks, ephemeral traces of past mobility. But now that engineers of today prefer to drill through the mountains instead of traversing them, will the old serpentine roads soon be abandoned, closed to protect the mountains from our highly motorized addiction to pleasure?

How will our children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren experience this mountain world? Will it still be part of their physical existence – the curves actually driven simply by electricity, hydrogen, synthetic fuel instead of gasoline? Or just virtually? As a proxy on their high-resolution monitors? As artifacts from long-forgotten eras, without their own souvenir pictures, without connection to real life? What role will mountains play in the next chapters of mankind, in a hundred, even a thousand years? The future of the mountains remains fiction – instead, let’s turn out attention to the present: Often it is precisely the nostalgia of the useless and irrelevant that holds a special allure over us. Robbed of their original function, the aesthetic dimension of these mountain roads and alpine passes increasingly comes to the fore. Their beauty, their promise of deceleration and authenticity. And so our view changes, too.

The alpine landscapes that Stefan Bogner creates in his photography have little to do with the lush fields of flowers and sun-drenched ski slopes in traditional travel brochures of the tourism and marketing industry. With their brown, arid meadows and vegetation, patchy snowfields, cliffs covered in moss and lichen, faded strips of asphalt, seas of fog and wisps of clouds – again and again, wisps of clouds – rather, his motifs and image construction follow the ideal of the Romantics, who in the 19th century discovered the Alps as an otherworldly gateway between man (small, finite) and the divine universe (large, infinite). The greatness – or sublime as English exhibition catalogues call the quality of Caspar David Friedrich’s work – of these mighty, rugged rock masses and formations, shaped by the movement of the continents over millions of years and untamed by mankind, blows like a cold wind on the back of the neck when looking at Bogner’s mountain worlds.

But the Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog – gazing into infinity with his back to the observer – can only partially serve as a figurehead for today’s Weltschmerz sufferers in their search for meaning. And thus, Stefan Bogner approached the Alps as we know them best: from a street perspective. This is what makes his many Alpine books and the Curves magazines all the more appealing – the reader always sits in the driver’s seat of a sports car, or hunkered over the handlebars of a racing bike. The fact that the cars and racing bicycles are invisible or only glimpsed as a distant man-made object set in an overwhelming landscape does not diminish the impression – indeed, viewers are left to simply imagine their own form of transport. Like in a flipbook, you can leaf through the most stunning mountain roads and alpine passes, experience the Gotthard curve by curve, the Stelvio Pass or the Furka in their existential imagery, even though you’re relaxing on the sofa with a glass of Lagrein wine in your hand.

These classic point-of-view shots, which allow the viewer to identify with the protagonist, these invisible curve hunters, are of course old acquaintances – we know them all too well from the movies of Alfred Hitchcock, Jonas Åkerlund, Gaspar Noé. And perhaps this perspective works well as a stylistic devise because many modern alpine passes of the 20th century, like the Susten Pass or the Grossglockner High Alpine Road, were even built if not staged as perceptual experiences based on a cinematographic model: as a rapid succession of light and shadow, close up and wide-open views, as visual rollercoasters. The motorist firmly buckled into a sports seat, the gaze fixed on what is happening ahead, and the cinema audience in their seats – they are children of the same era. Siblings in the spirit of a media dispositive, architecture that guides the view and that fully determines the perception.

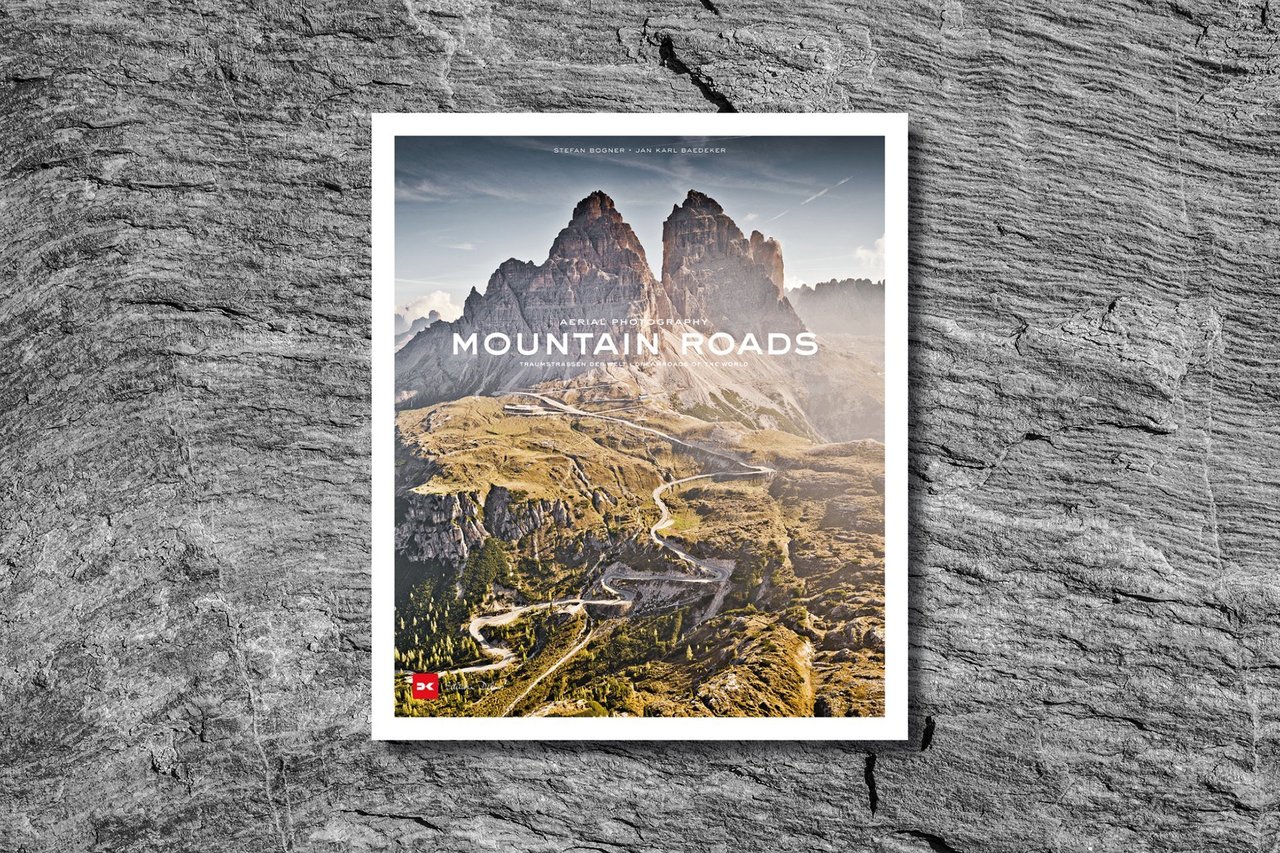

Those who have followed James Bond’s wild ride over the Furka Pass on screen can hardly drive this road without thinking about the fast cuts, squealing tires, the rapidly changing perspectives. The subjective view over the steering wheel creates authenticity – and yet the landscapes shown are and will remain of course fictional constructions, figments of the imagination. In Stefan Bogner’s work, the point of view is therefore joined by another, relativistic perspective: the bird’s eye view that transcends and permeates every real experience. Seen from above, real environments suddenly become abstract compositions in which the interplay between the flow of the road and the alpine topography and the skill of the architects and engineers are revealed. How daringly the Tremola snakes up the steep flanks of the mountain only becomes clear when seen from the air. The fascinating connection emerges here between tangible reality – readers can almost smell the snow, rock and summit bratwurst wafting from the images – and the metaphysical, authorial perspective from above.

The first glance does not reveal the creative process of Stefan Bogner’s aerial shots – and yet it is decisive for the effect of the images. They are not satellite images where even the steepest mountain peaks are flattened into two dimensions. They are also not drone shots, which often appear unreal in their perspective perfection. Rather, the photographer insists on climbing aboard a helicopter for his work, clipping on a safety harness, pulling a beanie over his ears and away he flies, up there, in the storm of the thermals with the noise of the rotor, sliding open the door and hanging over the side with his camera at the ready, always on the lookout for that special moment, the extraordinary shot, to the very last second before the ominous black cloudbank completely blocks the view of the serpentines below him and forces the pilot to turn back.

Stefan Bogner puts immense logistical effort into creating his mountain images. Likewise, the technical demands on equipment, lenses, processing and printing. Still, it is less about the perfect photography, the ideal interaction of all elements, the moment when the stars align. It is more about the charm of the unexpected, the magic of serendipity, which sometimes results in more than the sum of all its parts. So, the photographer returns again and again to the mountains, flying over countless summits and valleys, by helicopter or plane, in summer and winter. He documents deserted passes in the light of the first sunrays or hairpin bends in hibernation, only shadowy silhouettes under white avalanche sheets. Like the Tibetan pilgrims who repeatedly circumnavigate Mount Kailash on their knees in the quest for enlightenment, Stefan Bogner also circles the mountains that are sacred to him, over and over again. And then you understand: this is not about ticking items off a bucket list, the Seven Summits of a mountain photographer. It’s about a man’s love affair with a landscape. It’s the story of someone who just can’t get enough of soaking up the peaks and valleys; the changing weather, the colors, the structures, the topography, the road, the curves and bends, ramps and galleries, bridges and tunnels. And who allows himself to be constantly surprised by his own interpretation of the sublime, the breathtaking, eternal and yet so fragile world of the mountains.